Frequently Asked Questions About the Orthodox Church

by Fr. Steven Tsichlis

Many people believe that in order to be Christian, you must be a member of a Roman Catholic, Protestant or more recently, a non-denominational church. As Orthodox Christians, we are catholic, but not Roman Catholic. Catholic is a Greek word that means “wholeness, fullness, integrity” and, secondarily, “universal” and “open to all.” We confess the Christian faith in its fullness and our Church is open to everyone who confesses that faith and wants to live it. Evangelical comes from the Greek word that means “Gospel” or “Good News.” We are a Gospel-centered and Gospel-sharing community. But we are not Protestants. The root of the word “Protestant” is protest. We did not participate in the 16th century Reformation that protested, among other things, the sale of indulgences by the Roman Catholic Church of that time. Nor are we non-denominational, a popular term in contemporary American Christianity. Rather, we are pre-denominational, as our history goes back to the earliest Church, before any of the many Protestant denominations existed. And orthodox is a Greek word that means both “the true way to worship” and “straight thinking.” Attach it to the word “Christian” as we do and it describes a person trying to live according to the Gospel.

Because Orthodox Christianity is simply New Testament Christianity 2,000 years later it is quite different in a number of ways from Roman Catholicism and Protestantism. The following questions and answers drawn from a conversation between neighbors indicate both some important points of contrast as well as similarity:

Are you Jewish?

No. We’re most definitely Christians!

Oh, then, you’re like Orthodox Presbyterians?

No. We’re neither Protestant nor Roman Catholic.

Oh, you mean like “Eastern Orthodox”?

Yes, except that we as Americans are very much in and of “the West.” Ironically it is from the West that “the Eastern Orthodox Church” came to these shores some two hundred years ago through Alaska and California. Since that time Orthodox Christianity has been established a lasting presence in the U.S.

Is that like “Greek Orthodox” and “Russian Orthodox”?

Yes, but… the Orthodox Church is one Church. To be Greek Orthodox, Russian Orthodox, Romanian Orthodox or Serbian Orthodox is like being Irish Catholic, Italian Catholic, or Polish Catholic – it’s the same Church, the same faith, but rooted in a different country and culture. Currently, however, Church organization in North America is divided among several different “jurisdictions,” or governing bodies of varying national origins within the one Church. The doctrine and worship of each jurisdiction and parish is the same, though in some, languages other than English continue to be used in the services.

I thought there are just two kinds of Christians - Protestant and Catholic. How can you claim you are neither?

From the Orthodox point of view, Roman Catholicism is a medieval modification of the original Orthodox faith of the Church in Western Europe, and Protestantism is a later attempt to return to the original Faith. There is a certain sense in which, to our way of thinking, the Reformation did not go far enough or take the right direction.

We respectfully differ with Roman Catholicism on questions of papal authority, the nature of primacy within the Church, and a number of other consequent issues. Historically, the Orthodox Church is both “pre-Protestant” and “pre-Roman Catholic” in the sense that many modern Roman Catholic teachings (such as the dogmas of papal infallibility and the immaculate conception of the Virgin Mary) were developed much later in Christian history. The word catholic is a Greek word meaning “having to do with wholeness, fullness of faith.” We do consider ourselves “Catholic” in that sense of the word, that is, as proclaiming and practicing “the fullness of the Christian faith.” In fact, the full name of our Church is “The Orthodox Catholic Church.”

We find that Protestants readily relate to Orthodoxy’s emphasis on personal faith and the Scriptures. Roman Catholics easily identify with Orthodoxy’s rich liturgical worship and sacramental life. Roman Catholic visitors often comment, “in lots of ways your Liturgy reminds me of our old High Mass.”

Many of the polarities that exist between Protestants and Roman Catholics (i.e., “Word versus Sacrament” or “Bible versus Tradition” or “Faith versus Works”) have never arisen in the Orthodox Church. We believe that Orthodox theology offers Roman Catholics and Protestants a way in which apparently opposite differences can be reconciled.

Why do you call yourselves “Orthodox”?

The word orthodox was coined by the ancient Christian Fathers of the Church, the name traditionally given to the Christian writers in the first centuries of Christian history. Orthodox is a combination of two Greek words, orthos and doxa. Orthos means “straight” or “correct.” (It is also found in the word “orthopedics,” which in the original Greek means “the correct education of children.”) Doxa means at one and the same time “glory,” “worship” and “doctrine.” So the word orthodox signifies both “proper worship” and “correct doctrine.”

The Orthodox Church today is identical to the undivided Church of ancient times. It is the Church found on the pages of the New Testament. The 16th century Protestant Reformer Martin Luther once remarked that he believed the pure Faith of primitive Christianity is to be found in the Orthodox Church.

Then you must be a very conservative Church.

In current American usage, the words “conservative” and “liberal” are highly politicized categories and indicate a variety of often-conflicting viewpoints. Usually we don’t really fit either category very well.

For example, on seven major occasions during the first millennium of Christianity the leaders of the worldwide Church, from Britain to Ethiopia, from Spain and Italy to Turkey and Arabia, met to settle crucial issues of Faith in confronting false doctrines about our Lord Jesus Christ and the Holy Spirit. The Orthodox Church is highly “conservative” in the sense that we adhere to the teachings of those seven Ecumenical Councils to this day.

But that very “conservatism” in Christology and Trinitarian theology often makes us “liberal” in certain questions around the inherent dignity of all human beings, social justice and peace. We are also very conservative, or rather traditional, in the structures of our liturgical worship.

Which do you believe in: the Bible or Tradition?

A good short answer to this question is “Yes!” The question implies precisely the kind of polarity (i.e., “Bible versus Tradition”) which is not found in the Orthodox Christian worldview. “Tradition” or in Greek paradosis, is found very often in the New Testament both as a verb and a noun. (See 1 Corinthians 11:23, where literally translating the original Greek, Paul says “for I received of the Lord that which I also have traditioned to you . . . .” See also 1 Corinthians 11:2, and 2 Thessalonians 2:15 and 3:6.)

Tradition means “that which is handed over.” The New Testament carefully distinguishes between “traditions of men” and the Tradition, which is the Faith handed over to us by Christ in the Holy Spirit. That same Faith was believed and practiced several decades before the New Testament Scriptures were set down in writing and given canonical (i.e., official) status by the Church. We experience the Tradition as, to use the phrase of one contemporary Orthodox theologian, “the life of the Holy Spirit within the Church” and therefore timeless and ever timely, ancient and ever new.

We often distinguish between the Tradition (with a capital “T”) which is the Faith/Practice of the Undivided Church, and traditions (with a little “t”) which are local or national customs that may vary from country to country. Due to changing circumstances, sometimes cherished local customs must be altered or respectfully laid aside for the sake of the Tradition.

The Scriptures are the primary written witness to the Tradition of the Church. Orthodox Christians therefore believe the Bible, as the inspired written Word of God, is the heart of the Tradition. In the Scriptures all basic Orthodox doctrines and sacramental practice are either specifically set forth, or alluded to as already a practice of the Church in the first century A.D. The Tradition is also witnessed to by the decisions of the Seven Ecumenical Councils, the Nicene Creed, the writings of the Fathers and Mothers of the Church, the liturgical worship and iconography of the Church, and in the lives and witness of the saints and martyrs down through the centuries.

Do you Orthodox Christians really believe your elaborate worship is based on the Bible? I’d like to know where!

The Christian Church learned how to worship in the context of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem and in the Synagogue. The Lord Jesus and the 12 apostles were Jews. Again and again the New Testament tells us that the Lord Jesus, the apostles Peter, Paul and others worshipped regularly in Jewish houses of worship. (See for instance Luke 4:16; Acts 3:1; Acts 17:1-2.) We know that worship in the Temple was liturgical and sacrificial. We also know from archaeology, and from modern Jewish practice, that Synagogue worship was and is highly liturgical, i.e., communal, organized, ceremonial, and done decently and in good order (I Corinthians 14:40). The French Lutheran biblical scholar Oscar Cullman (1902-1999) demonstrates very convincingly in his little book Early Christian Worship that when John describes heavenly worship in the Book of Revelation, he is following the Hebrew custom of portraying Heaven’s worship in terms of earthly liturgy. The writers of the Bible thought of earthly worship as a “shadow” or “type” of Heaven’s liturgy. (See Isaiah 6, Hebrews 8:4-6.) In other words, a biblical passage such as the fourth and fifth chapters of the Book of Revelation gives us an accurate picture of a very early Christian worship service. That service very much resembles modern Orthodox worship. Orthodox worship is also very Scriptural in the sense that it is a kaleidoscopic mosaic of Scriptural quotations, paraphrases, references, and allusions with more than 98 direct quotes from the Old Testament and 114 from the New Testament woven into our prayers and hymns. Orthodox worship is, quite literally, “to pray the Bible!”

Apart from the fact that we worship in English, and use modern harmonies with our ancient melodies, our services are basically identical to those of the early Christian Church. For that reason our worship sometimes seems a bit “strange” to Protestant and Roman Catholic visitors. We often hear, “Your services are just beautiful, and the music is outstanding, but they just feel so different.”

It sounds as if you are rigidly bound by your Tradition. Does this mean it can’t change?

The Tradition of the Church, as a set of basic principles outlining our worldview, is a constant. Its very constancy, however, sometimes will even demand change. As an example of this, by Tradition our worship is to be celebrated in a language understood by the local worshipping congregation. This means the Tradition not infrequently requires a change in liturgical language. As another instance, the Tradition also requires repentance: constant change in ourselves as, through the guidance of the Holy Spirit, we grow spiritually and respond ever more fully to the call of God in Jesus Christ.

Do you have the Virgin Mary, Saints and confession “like the Catholics?” Do you pray for the dead?

There are some important points of contact between Orthodox and Roman Catholic belief and practice on these issues. There are also significant differences. To discuss them in depth is beyond the scope of this short summary. What follows is a brief statement of the Orthodox point of view on these questions.

We honor the Virgin Mary as “higher than the Cherubim and more glorious than the Seraphim” because she is the woman who gave birth to Christ Jesus who is the Word of God made flesh (and therefore, in Greek, the Virgin Mary is called Theotokos or the Mother of God). We call her blessed and think of her as the greatest of missionaries, for her unique mission was to bring the Word of God into the world. (See Luke 1:43, 48: John 1:1, 14; Galatians 4:4.)

We likewise honor the other great men and women in the life and history of the Church – patriarchs, prophets, apostles, preachers, teachers, evangelists, martyrs, confessors and ascetics – who committed their lives so completely to the Lord, as models of what it means to be fully and deeply Christian. These men and women are called “saints”, a word deriving from the ancient Latin word meaning “holy.” For example, we believe that men like the apostle Paul – in their devotion to Christ – led holy lives and that we are indeed to be imitators of him, as he was of Christ (1 Corinthians 4:16).

We also believe that in the risen Christ, prayer transcends the barrier between life and death and that those who have gone before us pray for us, as we remember them in our prayers. In Christ, we are one family, a communion of saints. (See Hebrews 12:1; 2 Timothy 1:16-18.)

As indicated in John 20:21-23, and James 5:14-16, we practice sacramental confession and forgiveness of sins. The presbyter (priest) conveys the sacramental presence of the crucified and risen Christ. In the context of the celebration of confession the priest conveys Christ’s forgiveness, not his own.

Does your church practice “Open Communion?”

In the strictest sense the Communion of the Orthodox Church is open to all repentant believers. This means we are glad to receive new members in the Orthodox Church. The Orthodox concept of “Communion” is totally holistic, and radically different from that of most other Christian groups. We do not separate the idea of “Holy Communion” from “Being in Communion,” “Full Communion,” “Inter-Communion” and complete “Communion in the Faith.” In the Orthodox Church therefore, to receive Holy Communion, or any other Sacrament (Mystery), is taken to be a declaration of total commitment to the Orthodox Faith. While we warmly welcome visitors to our services, it is understood that only those communicant members of the Orthodox Church who are prepared by prayer, almsgiving, fasting and confession will approach the Holy Mysteries.

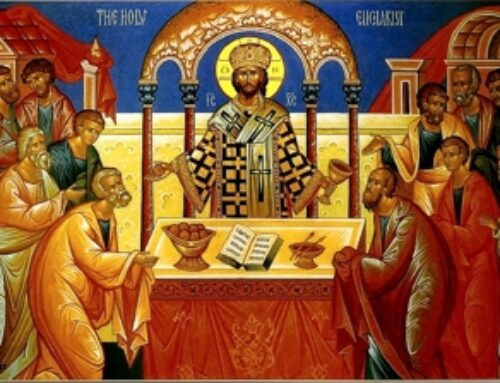

Why do you have all those pictures in your church?

Icons are not pictures in the sense of naturalistic representations. They are rather stylized and symbolic expressions of divinized humanity. (See 2 Peter 1:4; 1 John 3:2.) Icons for the Orthodox are sacramental signs of God’s great Cloud of Witnesses (Hebrews 12:1). We do not worship icons. Rather, we experience icons as windows into Heaven. Like the Bible, icons are earthly points of contact with transcendent Reality. In the original Greek of the New Testament Christ is called – several times – the icon (image) of God the Father. (See 2 Corinthians 4:4; Colossians 1:15; Hebrews 1:3.) We human beings were originally created to be icons of God (Genesis 1:27).

Isn’t all your old-fashioned doctrine and worship irrelevant to modern American life?

We believe that God really does exist! He is not the figment of pious imagination, a devout fiction or wishful thinking. God and His will is our “top priority” in life! We believe that the Word of God quite literally became Incarnate in Jesus of Nazareth. We believe the Lord Jesus literally rose from the dead in a real though transfigured and glorified physical body. We believe that life apart from God is hollow and meaningless. We notice that people today talk often of “the meaning of life,” “having meaningful relationships,” “the common good,” “the good of humanity,” “hope for the future of mankind” and so on. Also, various cults continue to attract many followers in all parts of our country. This indicates to us that people today are hungry for the answers we believe God has revealed through His Word, Who is Jesus Christ.

We believe ultimate human values are revealed to us by God, and serve as constant guides in the use of our steadily expanding scientific knowledge. We seek to evaluate technological advances in the light of those basic values. It is our experience that our venerable Liturgy and the ancient Christian doctrines about God and the meaning of human life are just as relevant today as yesterday. These define our basic values. We know the whole ancient Christian Faith as that which makes more sense than anything else in this world of constant change, confusion and conflict. God is the Source of all Meaning; we believe that “mankind’s noblest ideals” such as truth, beauty, freedom and love, are not “merely ideals,” but real characteristics of a real Lord.

In and through Christ Jesus, God reveals Himself in human terms and in human terminology as One who is at the same time a Trinity of Persons. The word “person” as used in classical Christian theology is not the singular form of “people”; God is not “Three people.” Person here means something similar to “I,” or “Subject,” as in the subject of a sentence. The One God is revealed as having three personal “Centers of Being.” God is therefore neither alone nor lonely, for the One Lord is also perfect Communion of Persons. God as Trinity is the model and source of human inter-personal communion and fellowship.

We were created to be capable of communion (mystical union) with God. Human matrimony is a favorite biblical image for this communion-relationship. Our capacity for divine communion was soon damaged by human error, stubbornness, and evil (i.e., sin). Because of God’s infinite love, our potential for communion with God has been restored, renewed, and transfigured by Christ Jesus in the Holy Spirit. Christ communicates His very life to us through His Scriptures and Sacraments. In Christ and the Holy Spirit we can and do experience varying degrees of a mystical union with God now in this life, and on a regular basis.

We believe that the purpose of human life is for us to become partakers of the divine nature (2 Peter 1:4) through the grace of the Holy Spirit, in prayer, the sacraments, in study of the Scriptures, fasting, self-discipline, and active love for others. All other human projects and purposes, however noble and important, remain secondary to that, which gives ultimate meaning to human existence.

This brief outline of the Orthodox Faith necessarily only touches upon a number of more involved issues. If you would like to find out more, we welcome your inquiries.

Some Facts about Orthodoxy

There are some 250 million Orthodox Christians in the world. Most Christians in Greece, Romania, Bulgaria and Serbia, Russia and the Ukraine are Orthodox.

Three million Americans are Orthodox Christians. Organized Orthodox Church life first came to America in 1794 with missionaries from old Russia who came to Alaska.

Centuries of vigorous Orthodox missionary activity across 12 times zones in northern Europe and Asia was halted by the Communists after the Soviet Revolution in 1917. Today Orthodox missions are active in Central and East Africa, Japan, Korea and many other parts of the world.

A Brief Statement of Faith

I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Creator of heaven and earth and of all things visible and invisible;

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all ages.

Light of Light, true God of true God, begotten, not created, of one essence with the Father through whom all things were made.

Who for us men and for our salvation, came down from heaven and was incarnate of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary

and became man.

He was crucified for us under Pontius Pilate and He suffered and was buried.

On the third day He rose according to the Scriptures.

He ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father. He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead. His Kingdom will have no end.

And In the Holy Sprit, the Lord, the Creator of Life, who proceeds from the Father,

who together with the Father and Son is worshipped and glorified, who spoke through the prophets.

In one, holy, catholic and apostolic church.

I confess one baptism for the forgiveness of sins.

I expect the resurrection of the dead and the life of the age to come.

Amen!