Confession: The Sacrament of Healing

By Jim Forest

Confession! The word makes us nervous, touching as it does all that is hidden in ourselves: lies told, injuries caused, things stolen, friends deceived, people betrayed, promises broken, faith denied — these plus all the smaller actions that reveal the beginnings of our sins. Confession is painful, yet a Christian life without confession is impossible.

Confession is a major theme of the Gospels. John the Evangelist warns us not to deceive ourselves. “If we say we have no sin, we deceive ourselves and the truth is not in us. If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just, and will forgive our sins.” (1 John 1:8-9) Even before Christ began his public ministry, we read in Matthew’s Gospel that John the Baptist required confession of those who came to him for baptism in the River Jordan for a symbolic act of washing away their sins: “And they were baptized by [John] in the river Jordan, confessing their sins.” (Matthew 3:6) Then there are those remarkable words of Christ to Peter: “I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.” (Mt 16:19) The keys of binding and losing sins were given not only to a one apostle but to all Christ’s disciples, and — in a sacramental sense — to any priest who has his bishop’s blessing to hear confessions.

What is sin? There have been countless essays and books in recent decades which have dealt with human failings under various labels without once using the three-letter word that has more bite than any of its synonyms: sin. Actions traditionally regarded as sinful have instead been seen as natural stages in the process of growing up, a result of bad parenting, a consequence of mental illness, an inevitable response to unjust social conditions, pathological behavior brought on by addiction, or even as “experiments in being.” But what if I am more than a robot programmed by my past or my society or my economic status and actually can take a certain amount of credit — or blame — for my actions and inactions? Have I not done things I am deeply ashamed of, would not do again if I could go back in time, and would prefer no one to know about? What makes me so reluctant to call those actions “sins”? Is the word really out of date? Or is the problem that it has too sharp an edge?

The Jewish approach to sin tends to be concrete. The author of the Old Testament Book of Proverbs lists seven things which God hates: “A proud look, a lying tongue, hands that shed innocent blood, a heart that plots wicked deeds, feet that run swiftly to evil, a false witness that declares lies, and he that sows discord among the brethren.” (6:17-19)

As in so many other lists of sins, pride is given first place. The craving to be ahead of others, to be more valued than others, to be more highly rewarded than others, to be able to keep others in a state of fear, the inability to admit mistakes or apologize — these are among the symptoms of pride. Pride opens the way for countless other sins: deceit, lies, theft, violence, and all those other actions that destroy community with God and with those around us.

“We’re capable of doing some rotten things,” the Minnesota storyteller Garrison Keillor notes, “and not all of these things are the result of poor communication. Some are the result of rottenness. People do bad, horrible things. They lie and they cheat and they corrupt the government. They poison the world around us. And when they’re caught they don’t feel remorse — they just go into treatment. They had a nutritional problem or something. They explain what they did — they don’t feel bad about it. There’s no guilt. There’s just psychology.”

For the person who has committed a serious sin, there are two vivid signs — the hope that what I did may never become known; and a gnawing sense of guilt. It is a striking fact about our basic human architecture that we want certain actions to remain secret, not because of modesty but because there is an unarguable sense of having violated a law more basic than that in any law book — the “law written on our hearts” that St. Paul refers to (Rom 2:15). It isn’t simply that we fear punishment. It is that we don’t want to be thought of by others as a person who commits such deeds. One of the main obstacles to going to confession is dismay that someone else will know what I want no one to know.

![]() One of the oddest things about the age we live in is that we are made to feel guilty about feeling guilty. A sense of guilt — the painful awareness of having committed sins — can be life renewing. Guilt provides a foothold for contrition, which in turn can motivate confession and repentance. Without guilt, there is no remorse; without remorse there is no possibility of becoming free of habitual sins. A blessed guilt is the pain we feel when we realize we have cut ourselves off from that divine communion that radiates all creation. It is impossible to live in Godless universe, but easy to be unaware of God’s presence or even to resent it.

One of the oddest things about the age we live in is that we are made to feel guilty about feeling guilty. A sense of guilt — the painful awareness of having committed sins — can be life renewing. Guilt provides a foothold for contrition, which in turn can motivate confession and repentance. Without guilt, there is no remorse; without remorse there is no possibility of becoming free of habitual sins. A blessed guilt is the pain we feel when we realize we have cut ourselves off from that divine communion that radiates all creation. It is impossible to live in Godless universe, but easy to be unaware of God’s presence or even to resent it.

It’s a common delusion that one’s sins are private or affect only a few other people. To think our sins, however hidden, don’t affect others is like imagining that a stone thrown into the water won’t generate ripples. As Metropolitan Kallistos Ware has observed, “There are no entirely private sins. All sins are sins against my neighbor, as well as against God and against myself. Even my most secret thoughts are, in fact, making it more difficult for those around me to follow Christ.” Far from being hidden, each sin is another crack in the world.

There are only two possible responses to sin: to justify it, or to repent. Between these two there is no middle ground. Justification may be verbal, but mainly it takes the form of repetition: I do again and again the same thing as a way of demonstrating to myself and others that it’s not really a sin but rather something normal or human or necessary or even good. “Commit a sin twice and it will not seem a crime,” notes a Jewish proverb.

Repentance, on the other hand, is the recognition that I cannot live any more as I have been living, because in living that way I wall myself apart from others and from God. Repentance is a change in direction. Repentance is the door of communion. It is also a sine qua non of forgiveness. Absolution is impossible where there is no repentance.

Confession as a social action: It is impossible to imagine a healthy marriage or deep friendship without confession and forgiveness. If you have done something that damages a relationship, confession is essential to its restoration. For the sake of that bond, you confess what you’ve done, you apologize, and you promise not to do it again, and you do everything in your power to keep that promise. Confession restores our communion with God and with each other.

It is never easy admitting to doing something you regret and are ashamed of, an act you attempted to keep secret or denied doing or tried to blame on someone else, perhaps arguing — to yourself as much as to others — that it wasn’t actually a sin at all, or wasn’t nearly as bad as some people might claim. In the hard labor of growing up, one of the most agonizing tasks is becoming capable of saying, “I’m sorry.” Yet we are designed for confession. Secrets in general are hard to keep, but un-confessed sins not only never go away but have a way of becoming heavier as time passes — the greater the sin, the heavier the burden. Confession is the only solution.

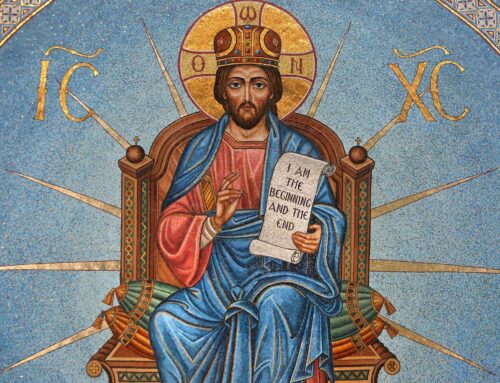

To understand confession in its sacramental sense, one first has to grapple with a few basic questions: Why is the Church involved in forgiving sins? Is priest-witnessed confession really needed? Why confess at all to any human being? In fact, why bother confessing to God even without a human witness? If God is really all-knowing, then he knows everything about me already. My sins are known before it even crosses my mind to confess them. Why bother telling God what God already knows?

Yes, truly God knows. My confession can never be as complete or revealing as God’s knowledge of me and all that needs repairing in my life. A related question we need to consider has to do with our basic design as social beings. Why am I so willing to connect with others in every other area of life, yet not in this? Why is it that I look so hard for excuses, even for theological rationales, not to confess? Why do I try so hard to explain away my sins until I’ve decided either they’re not so bad or might even be seen as acts of virtue? Why is it that I find it so easy to commit sins yet am so reluctant, in the presence of another, to admit to having done so?

We are social beings. The individual as autonomous unit is a delusion. The Marlboro Man — the person without community, parents, spouse, or children — exists only on billboards. The individual is someone who has lost a sense of connection to others or attempts to exist in opposition to others — while the person exists in communion with other persons. The language we speak connects us to those around us. The food I eat was grown by others. The skills passed on to me have slowly been developed in the course of hundreds of generations. The air I breathe and the water I drink is not for my exclusive use but has been in many bodies before mine. The place I live, the tools I use, and the paper I write on were made by many hands. I am not my own doctor or dentist or banker. To the extent I disconnect myself from others, I am in danger. Alone I die, and soon. To be in communion with others is life.

Because we are social beings, confession in church does not take the place of confession to those we have sinned against. An essential element of confession is doing all I can to set right what I did wrong. If I stole something, it must be returned or paid for. If I lied to anyone, I must tell that person the truth. If I was angry without good reason, I must apologize. I must seek forgiveness not only from God but from those whom I have wronged or harmed.

Confessing to anyone, even a stranger, renews rather than contracts my humanity, even if all I get in return for my confession is the well-worn remark, “Oh that’s not so bad. After all, you’re only human.” But if I can confess to anyone anywhere, why confess in church in the presence of a priest? Confession is a Christian ritual with a communal character. Confession in the church differs from confession in your living room in the same way that getting married in church differs from simply living together. The communal aspect of the event tends to safeguard it, solidify it, and call everyone to account — those doing the ritual, and those witnessing it.

My confession is an act of reconnection with God and with all the people and creatures who depend on me and have been harmed by my failings and from whom I have distanced myself through acts of non-communion. The community is represented by the person hearing my confession, an ordained priest delegated to serve as Christ’s witness, who provides guidance and wisdom that helps each penitent overcome attitudes and habits that take us off course, and who declares forgiveness and restores us to communion. In this way our repentance is brought into the community that has been damaged by our sins — a private event in a public context.

“It’s a fact,” writes Fr. Thomas Hopko, Dean Emeritus of St. Vladimir’s Seminary, “that we cannot see the true ugliness and hideousness of our sins until we see them in the mind and heart of the other to whom we have confessed.”

Key elements in confession: The late Fr. Alexander Schmemann (1921-1983) provided this summary of the three key areas we must examine in confession:

Relationship to God: Questions on faith itself, possible doubts or deviations, inattention to prayer, neglect of liturgical life, fasting, etc.

Relationship to one’s neighbor: Basic attitudes of selfishness and self-centeredness, indifference to others, lack of attention, interest, love. All acts of actual offense — envy, gossip, cruelty, etc. — must be mentioned and, if needed, their sinfulness shown to the penitent.

Relationship to one’s self: Sins of the flesh with, as their counterpart, the Christian vision of purity and wholesomeness, respect for the body as an icon of Christ, etc. Abuse of one’s life and resources, absence of any real effort to deepen life; abuse of alcohol or other drugs; cheap idea of “fun,” a life centered on amusement, irresponsibility, neglect of family relations, etc.

Finding a confessor: A good confessor will help us become better at hearing conscience and becoming ever freer in an increasingly God-centered life. Fortunately good confessors are not hard to find. Usually your confessor is the priest who is closest, sees you most often, who knows you and the circumstances of your life best: a priest of your parish. Do not be put off by your awareness of what you perceive as his relative youth, or his personal shortcomings, or the probability that he possesses no rare spiritual gifts. Keep in mind that each priest goes to confession himself and may have more to confess than you do. You confess not to him but to Christ in his presence. He is the witness of your confession — you do not require and will never find a sinless person to be that witness. (The Orthodox Church tries to make this clear by having the penitent face not the priest but an icon of Christ.) What he says by way of advice can be remarkably insightful or brusque or seem to you a cliché and not very relevant, yet almost always there will be something helpful if only you are willing to hear it. Sometimes there is a suggestion or insight that becomes a turning point in your life. If he imposes a penance — normally increased prayer, fasting, and acts of mercy — it should be accepted meekly, unless there is something in the penance which seems to you a violation of your conscience or of the teaching of the Church as you understand it.

Don’t imagine that a priest will respect you less for what you reveal to Christ in the priest’s presence. Don’t imagine that he is carefully remembering all your sins. “Even a recently ordained priest will quickly find that he cannot remember 99 percent of what people tell him in confession,” one priest told me. He said it is embarrassing to him that people expect him to remember what they told him in an earlier confession. “When they remind me, then sometimes I remember, but without a reminder, usually my mind is a blank. I let the words I listen to pass through me. Also, so much that I hear in one confession is similar to what I hear in other confessions — the confessions blur together. The only sins I easily remember are my own.” One priest told me: “I am just a fellow sinner trying to stay on the path.”

A Russian priest who is spiritual father to many people once told me about the joy he often feels hearing confessions. “It is not that I am glad anyone has sins to confess but when you come to confession it means these sins are in your past, not your future. Confession marks a turning point and I am the lucky one who gets to watch people making that turn!