Worship, Beauty and the Desire for God

Excepted from At the Corner of East and Now

by Frederica Mathewes-Green

Beauty is that which opens our eyes to the majesty of God and moves us to desire Him. Worship is not just an intellectual grasping of truths but a process of falling in love. Beauty opens us to adoration and a craving for God begins to take root. Without this, our love for Him may be polite, respectful and even theologically accurate, but it lacks the headlong abandonment that should characterize a relationship between lover and beloved.

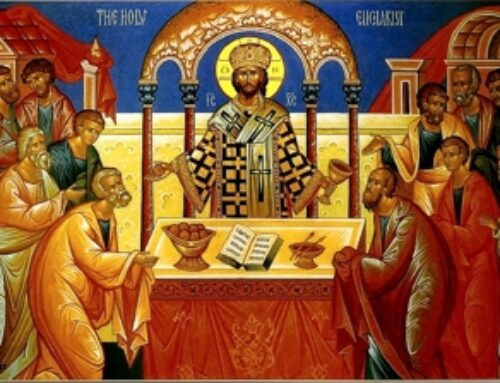

Modern American church architecture seldom shows regard for beauty; in fact, contemporary “worship spaces” often look like they’ve been designed to be lecture or entertainment spaces. Other important activities, like fellowship and education, have somehow invaded the time that should be set aside for falling down in awe before God. Orthodox worship is quite elaborate, even voluptuous with beauty. Extravagant but not formal, fancy but not fussy, our worship is like a big family Christmas dinner, with the best linens and finest dishes and everyone having a hearty time.

Worship was always meant to be gloriously, delightfully beautiful. This was true even in the time of Moses. Although His people were wandering the desert in tents, God commanded them to construct a tabernacle for worship that was staggeringly elaborate. The directions given in the Book of Exodus require gold, silver, precious stones, blue and purple cloth, embroidery, incense, bells and anointing oil. The pattern continues in the visions of the prophets, where God appears in glorious settings. Isaiah sees Him “high and lifted up,” wearing a robe with a voluminous train, while soaring angels chant a hymn and the smoke of incense fills the Temple (Isaiah 6). Daniel pictures the entrance of the Son of Man into the throne room of the Ancient of Days (Daniel 7:9-14). In the last book of the Bible, St. John has a vision of heavenly worship that includes precious stones, gold, thrones, crowns, white robes, crystal and incense (Revelation 4). From the beginning to the end of Scripture, worship is accompanied by great beauty.

As a result, Orthodox worship engages all the senses: we touch and kiss those things we venerate, smell incense and beeswax candles, taste bread and wine, and hear chanting and hymns. The sense of vision has the most to savor: we see the priest moving through the congregation carrying the brocade-draped gifts, preceded by a cross and candles carried in procession, surrounded by icons, and our friends and fellow worshippers bowing and praying as the smoke of incense swirls around us. The body is good and we worship with our whole bodies.

However, beauty is not to become an end in itself; mere ceremonialism would be a circular exercise and ultimately dead. But when entered with expectant joy, nothing opens the heart to deeper worship like beauty. In his Confessions, St. Augustine – the fourth century bishop of Hippo in north Africa – wrote of the passage through beauty into passionate love for God: “Late it was that I loved You, beauty so ancient and so new, late I loved You! And look, You were within me and I was outside and there I sought for You; in my ugliness I plunged into the beauties You had made. You were with me but I was not with You. You called, You cried out, You shattered my deafness, You flashed, You shone, You scattered my blindness. You breathed perfume and I drew in my breath and I pant for You. I tasted and I am hungry and thirsty. You touched me and I burned for Your peace.”

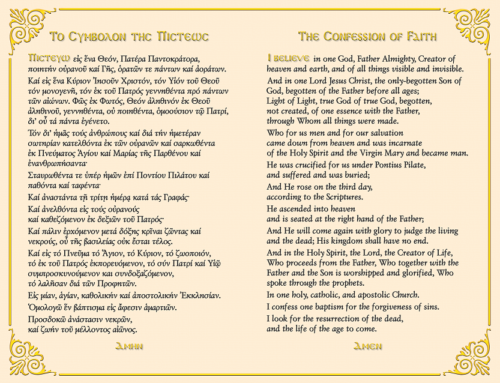

I drive carpool, write e-mail, read the paper, go to the mall, pop in a DVD. None of this matters; all of it could blow away overnight. What does matter is this slim golden thread: the Liturgy that begins each Sunday morning in my church and reaches its fulfillment in the moment I receive communion. Prayer spills backward and forward from that moment, wrapping me into union with God. It’s the work of a lifetime that stretches on beyond my earthly life. This perspective is backward from the usual. What happens in church is the most important thing; what happens in the rest of my life seems transient and contingent. The Liturgy is whole and beautiful; the rest of my life seems random and bumpy. When death strips away from me all the shreds of foolishness, self-indulgence, gossip and greed, this will remain, one of the few things to remain. In the moment after communion, I press my lips against the chalice, a kiss of surrender, veneration and gratitude. It is the one true centering moment of my oblivious cycling days and weeks. On the chalice I see the face of Christ painted in enamel. I look at Him and He looks at me.

The emotions I find prompted by walking the path Orthodoxy teaches are complex and hard to describe: the overwhelming and deliciously terrifying riptide of God’s love; the rapturous joy of weeping over my sins; the sweet, stinging desire to bring others to see the beautiful face of Jesus.

We are and will be ourselves: redeemed, exulting and charged with light, fulfilling the task we were created for, “destined and appointed to live for the praise of His glory” (Ephesians 1:12).